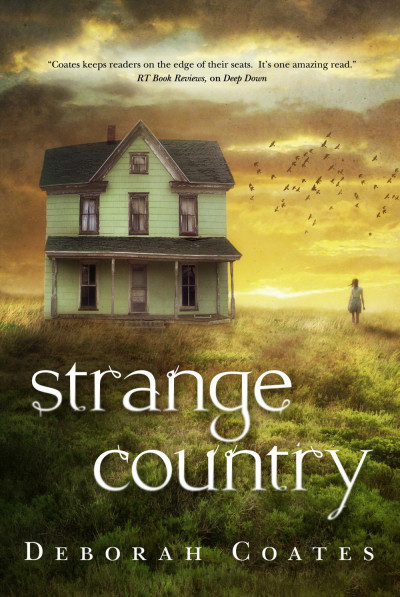

Check out Deborah Coates’ Strange Country, the third book featuring psychic Hallie Michaels, available May 27th from Tor Books!

Hallie Michaels had hoped things would finally settle down; that she and Boyd would find more time to spend together, and that the ghosts she attracts would stay in the cemeteries where they belong.

But on a wintry night in mid-December, a woman is murdered with a high-powered rifle. Not long after, another of West Prairie City’s citizens is killed in exactly the same way, drawing the attention of state investigators. But the connection between the victims is not easily uncovered.

Meanwhile, Hallie finds a note tied to post outside her home. “What do you fear most?” it asks, accompanied by a set of map coordinates…

1

It was three o’clock in the morning and the car had been parked in the same spot since the night before, had been there long enough that it iced over; the ice had half-melted and it iced over again so that it now looked permanent, like brittle armor. A Toyota, twenty years old, maybe a bit more, a nice car when it was new and it still looked pretty good, with nothing more than a little rust along the wheel wells. There was a web of spidering cracks in the back window on the passenger side, from a kicked-up stone or a hard stab with something pointed, not much yet, but as warm days and cold nights heated and cooled the glass, the cracks would spread.

Boyd Davies left his patrol car running, light from the open driver’s door spilling out, frost-white exhaust puffing out the rear. He shrugged his jacket up close and shone a flashlight at the car, the yellow beam bouncing off the icy windows. West Prairie City was quiet as a tomb. That’s what people said—quiet as a tomb, because no one else was around, because there was that peculiar sense of emptiness that came with early morning and loneliness and cold. Boyd checked the license plate, had to scrape ice and old dirt away to read it. South Dakota plates, but not local. He went back to his car and called it in, sat in the driver’s seat with the door still open.

It was cold and clear, but there wasn’t much wind. Boyd liked it, liked this time of year when winter was still heavy in the clouds and in the pale sun, when the temperature still hovered down in frostbite territory. He liked the way the grass lay over, the way the trees looked, stark and forbidding, liked the faint hint of a promise of warmth underneath all of it, something changing in the wind and the slant of the sun in the afternoons. It was mid-March and it felt like it had been winter forever, but spring would come.

It always came.

Dispatch came back and asked him to repeat the license plate, which he did. A coyote trotted down the middle of the street, stopped in the wash of his headlights, its eyes gleaming. A moment passed, watched and watching; then the radio crackled and the coyote slipped sideways into the shadows.

“Go ahead,” Boyd said when the dispatcher, Chelly Sweet, who was new, asked if he was available.

“That plate belongs to a 1987 Toyota Corolla, light blue, registered to a Tommy Ulrich. You want the address?”

“Yes.”

She read off an address in Rapid City, on the west side, Boyd thought, though he’d have to look it up to be sure. “Phone number?”

“Hold on,” she said. He could hear papers and the soft sound of computer keys.

“Yeah, looks like he called in earlier,” Chelly said. “Said he was in town yesterday evening—not, yesterday, like eight hours ago. The night before that. His car broke down and he’s getting someone to tow it.” She made an irritated noise. “Somebody just wrote it down on a scrap of paper. There’s no call record.” She sighed. “Probably the new dispatcher.” Like the extra two weeks’ experience she had made all the difference between sloppiness and proficiency. “Sorry.”

“Thanks,” Boyd said. “It’s fine.”

He fastened his seat belt and closed the door. Templeton had its own two-person police force, but the rest of the county was his—the sheriff’s department. Nights like this when it was just him, the central dispatcher, and the overnight cashier down at the Gas ’Em Up on CR54, he felt as if it had all been created just for him, as if the wide-open prairie and the distant smattering of lights at scattered ranches and mobile homes and crossroads were a separate world, his world.

He drove out of West Prairie City and headed south. He’d swing down past the ranch, though he’d already been that way earlier. It pulled at him, that ranch, so that he always knew where it was in relation to where he was, like magnetic north or homing pigeons.

Three cars passed him on the long loop, enough traffic so at this hour—three in the morning in the middle of the week—he watched them close. A cold dry wind blew out of the northwest. A tumbleweed bounced onto the road, hit the side of the car with a hollow scratch, and was gone somewhere behind him. A half mile later, he slowed to turn back onto the county road, no lights out here other than the stars and his own headlights. There was something ahead, a shadow in the twilight at the edge of his high beams. He slowed. Coyote. Another one. He tapped the brakes. Light from the coyote’s eyes reflected straight back at him, sharp and otherworldly. It trotted toward him along the road. When it drew parallel to the car, it turned its head and seemed to look directly at him before it angled across the old pavement and disappeared back into the night and the prairie.

Boyd idled his car. A vast nothingness surrounded him. Darkness and grass, wind and cold. He put his foot back on the gas, put a hand up to check the set of his collar, smooth the flap of his shirt pocket, brush nonexistent dust from the yoke of the steering wheel—so automatic, he barely noticed that he did it.

He felt a familiar tug as he passed the end of the drive up to Hallie’s ranch, like something real, like a wire. He didn’t answer it. It was past three, he was on duty, and he wasn’t that guy. The one who signed in, picked up his car, then drove home to sleep a few hours when he was supposed to be on patrol. He would never be that guy. Though he’d met guys like that—one or two—in the five years he’d been a police officer, met them at out-of-town trainings where they bragged in the bar after class. He didn’t understand—understood the pull, but didn’t understand—couldn’t—the dereliction. Because it was a promise, not to the job, but to the people in the towns and on the ranches. A promise that he would be where he said he was and that he would be ready. People said he was a Boy Scout, all honor and duty and service.

And he was.

So, there wasn’t any question when he passed Hallie’s drive that he would drive past. No question that patrolling an empty road was more important than to see her, hear her say—as she did—“Jesus, Boyd, it’s three o’clock in the morning.” More important than her lips against his, the clean soap scent of her hair, the soft exhale of her breath against his neck.

Lately there’d been an on-again, off-again feel to their relationship, not on his side, but on hers. He liked her, liked her a lot, maybe loved her, though it wasn’t a word he said quickly and when he did say it, he meant it honestly and deeply. But like her? Love parts of her like coming home? Yes. He liked the way she thought and even the way she acted, impulsively but worried about the consequences. Or acknowledging them but going ahead anyway. And he liked her, liked the way they fit together, opposite and yet the same.

After Hollowell, after the walls between the living world and the under had rebuilt themselves, after Hallie had told him what happened at the end—because he didn’t, had never remembered on his own. After all that, she’d been different. Maybe no one else noticed. He’d figured it was the result of everything that happened, not just killing Travis Hollowell the way she had, but also the way her sister, Dell, had died, the way Hallie herself had been forced out of the army, the way Pabby’d died and Beth had disappeared and Death, especially Death who had asked her to take his place in the under, to control the reapers, the harbingers, and the unmakers. It was as if she’d decided, why commit to anything? And that would weigh on her, he knew, because whether she recognized it or not, it was what she did—commit—to everything she did.

Whatever it was that bothered her, it was evident in their relationship these days, three steps forward, two steps back.

The radio crackled, almost startling him.

“Are you there?” Chelly Sweet’s voice sounded thin like old wire, like she thought maybe the world had disappeared in the last thirty minutes, like if she looked outside, there would be nothing but flat and dark and empty, which the prairie wasn’t, not empty, and not as flat as people thought it was.

“Go ahead,” he said. Precise as he was, he didn’t bother to identify himself. This time of night he was the only one answering.

“Got a call from a woman over on Cemetery. Says she thinks she has a prowler.” She gave him the address, which he punched into the GPS even though he didn’t need it, knew pretty much where every occupied house in the county was. He flipped on the lights and did a quick U-turn.

No siren.

No one would hear it anyway.

Twenty minutes later he pulled to a stop in front of the address Chelly had given him. It was an ordinary house, vaguely Victorian, but with no extra flourishes—no shingle siding or fancy paint, the porch had been enclosed years ago so that it faced the street white and stark and blockish, seeming to glow in the early morning darkness. Boyd turned off the engine and climbed out of the car. He zipped his jacket against the cold, slipped the hem up over his holster so he could reach his gun if he had to, and stood for a moment, assessing. The narrow front sidewalk had a crack running lengthwise and jagged through the middle of three separate sections. There was no yard light, no porch light, though a dim glow shone through the closed curtains of the inside porch window.

Boyd checked up and down the street. Wind burned across his cheekbones, cold and dry. Cemetery Road was on the north edge of West Prairie City. The cemetery for which the road was named occupied two lots directly across the street with an open field gone to grass and the county road beyond it. To the east of the cemetery sat a two-story-and-attic Queen Anne; to the west, a three-bedroom, no-frills ranch house built nearly a hundred years later. Three houses down, there was a light on in a second-floor bedroom, a garage light on in the house across, but otherwise the entire neighborhood was dark and quiet.

He skirted the house once: straggly shrubs underneath the porch windows in front, a single car garage down a narrow drive, a long row of overgrown privet along the garage, a big old maple tree in the center of the backyard with a few clusters of dried leaves rattling in the wind. There was a small back porch, enclosed like the front one, and in the east side yard, a row of paving stones, like someone had once intended a garden, but had run out of steam. No sign of a prowler, but the ground was frozen hard and there was no snow to leave tracks.

His knock on the rattly porch door sounded like a trio of gunshots, too loud for three o’clock in the morning. He waited. There was no movement behind the curtained windows where he presumed the living room was, no sound of footsteps approaching the door. He knocked again.

Finally the inside door opened and he saw, framed against the hall light, who it was who’d called—Prue Stalking Horse, who worked as a bartender down at Cleary’s and who always seemed to know things, whether she was willing to talk about those things or not. Boyd dropped a step down and waited for her to open the porch door and let him in.

She was tall, though not as tall as he was, with long white-blond hair, high cheekbones, and light blue eyes. There was a certain agelessness about her, but he’d never been able to figure out if that was because she really did look young or because she so rarely smiled or showed any sort of intense emotion.

He’d dreamed about her once.

Not—yeah, not in that way.

Boyd’s dreams were, or at least had always been, about events that were going to happen. He’d dreamed about Prue maybe four months ago, just after Hallie came back to Taylor County, after Martin and Pete died, after the end of Uku-Weber, but before the rest of it. It had been a short dream, barren landscape, gray skies—not cloudy skies, but a flat gray, like old primer or warships. There’d been three people in the dream, all of them so far away, they’d seemed to him like nothing more than dark silhouettes, and yet he’d known just from their dark profiles who two of them were—Prue Stalking Horse and Hallie Michaels. The third figure wasn’t someone he knew, or at least not someone he recognized within the context of the dream. He’d known it was that person, the unrecognizable one, who was important, who could have answered his questions, if he’d known which questions to ask. Of all of them, that third person was the one, in the dream, who knew exactly what was coming.

Tonight, Prue’s hair was smoothed back flat and tight, caught up in a neat knot at the nape of her neck. She wore an oversized denim shirt with old paint stains and black leggings to her ankles. Her feet were bare despite the late hour and the freezing temperatures.

Boyd held the door as he entered, then let it close slowly behind him. Prue still hadn’t turned on a porch light, so they stood in a sort of gray twilight illuminated only by the streetlights out along the road and the light inside in the hallway. The enclosed porch was a clutter of mismatched furniture, old rag rugs, and cardboard boxes stacked three high. “You reported a prowler,” Boyd said, his inflection settling the sentence somewhere between a statement and a question.

She turned away without answering him and walked back into the house. Boyd took a last look at the porch and the yard just beyond the windows and followed her inside. He wondered if this was one of those calls that came in the middle of the night sometimes, when sunrise seemed infinitely far and loneliness crowded in. People called because they couldn’t admit the real problem, that there was no sound in the house except their own breath moving in and out of their lungs. They called with whispered voices—something outside, they’d say, please come. Prue Stalking Horse had never struck Boyd as that sort of person. But then, people weren’t always who you thought they were.

The living room was dark, shades pulled tight over double windows north and east. Like the porch, it was full of mismatched furniture, mostly overstuffed chairs upholstered in faded chintz and small side tables with delicately turned legs, everything looking like it was bought at church sales and auctions after people died. The room smelled like lemon polish and carpet shampoo, though dust danced along a stray shaft of gray light from the floor lamp by the north windows.

“I heard a sound,” she said.

“In the house or outside?” he asked.

“Out… outside.” She stumbled over the word and it was the first sign Boyd had seen that she was even a little nervous. She didn’t wring her hands or tug at her clothes. She didn’t stare uncomfortably at his face as if looking for a sign that he believed her or understood, that he could stop whatever it was that had frightened her. She swallowed and continued, her voice smoothing out as she spoke. “We close at midnight on weeknights,” she said. “I usually get home around twelve forty or so, after I let the cleaning crew in and cash out. It’s not far. A mile, maybe?” Like it was a question. Like he would know the answer. “Sometimes in summer, I walk,” she said.

“But you drove tonight.”

Boyd could be patient. It annoyed Hallie, when he was patient. Hallie acted. Even when they didn’t know anything, even when there were important questions still to be answered, she preferred to do something. But patience worked. In this job, sometimes patience was all he had.

2

After a moment that was mostly silent, Boyd unzipped his jacket halfway, unbuttoned the flap on his shirt pocket, and pulled out a small notebook and a ballpoint pen. He clicked the top of the pen and flipped the notebook open to an empty page. He did it all slowly and deliberately, wanted to give her time to see him do it, to take a breath, to get what she wanted to tell him straight in her head.

She blinked when he clicked his pen, looked at the notebook in his left hand, at the pen in his right, then looked at him. “Yes,” she said. Another brief pause. “Well, yes.” She made a gesture toward the hall. “Let’s go back to the kitchen, Deputy…” She paused again.

“Davies.”

“Davies,” she repeated. The word sounded rich, the way she said it, as if it described azure skies, mountain meadows, the faint sweet scent of clover in late spring, and the lazy hum of bumblebees. Boyd looked at her more closely. “I’ll make coffee,” she said. As if this were a social call, as if whatever the danger was, whoever the prowler was, it was over.

Or she wanted to believe it was.

The kitchen was a sharp contrast to the living room, bright and warm, the walls pale yellow, the trim bright white, accessorized in sage green and brick red with stainless-steel appliances, granite countertops, and a stone tile floor. Boyd removed his jacket, hung it on a chair, and sat.

One of the lights over the stove buzzed. The room smelled of nutmeg and freshly turned soil. The door to the cellar was wide open, though Prue had to walk awkwardly around it when she went to the counter. The back door was closed and locked, chained. There were locked dead bolts below and above the doorknob. Both looked brandnew. Not a usual thing—triple locks—for West Prairie City, South Dakota.

Prue’s next words seemed to echo Boyd’s thoughts. “I don’t lock my doors. Usually. No one does around here. But lately, there’s been… well, it’s seemed like a good idea. When I got home tonight, the light was on by the garage. I didn’t think a lot of it. It comes on when there’s a storm, when the wind is strong, or a raccoon wanders through.” She put the filter in the coffeemaker, added water from the tap, and turned it on. She took two white cups with a chased silver design and matching saucers from the cupboard. When she set the cups and saucers on the table, her right hand shook and one of the cups jumped sideways. Boyd caught it before it fell and set it back on the saucer. “Thank you,” Prue said. For a moment, there was just the sound of the coffeemaker and the sharp odor of brewing coffee.

Prue sat down across from Boyd. She took hold of one of the cups by the handle and moved it back and forth as if to watch the silver catch the light. Boyd’s radio crackled. When the coffee finished brewing, Prue retrieved the pot. She poured coffee into each of the cups and slid one toward Boyd. She didn’t ask if he wanted cream or sugar, and he didn’t know if it didn’t occur to her or if she already knew he didn’t.

Boyd put his arm on the table and looked at her, though she wasn’t looking at him. “The prowler,” he said.

“I came in the back door,” she said, as if she’d simply been waiting for him to ask before she continued. “It was closed, but I realized when I grasped the doorknob that it wasn’t latched. That was the first thing. The light over the sink was on, as I’d left it. Nothing seemed to be disturbed. Then I heard it. A noise from upstairs.” She looked at him then, which she hadn’t done since she’d sat down, had told him the story while looking down at the coffee in her cup, like secrets had been written there. Or she was writing them as she spoke. “That’s when I called you.”

Boyd didn’t say, Why didn’t you tell me you heard a noise upstairs when I walked in the door? Why did you tell me the prowler was outside when you already knew he wasn’t? Because she hadn’t and they couldn’t go back and do it over.

Instead, he crossed to the back door and checked that it really was locked even though there were three locks and it was obvious that it was. “Stay here,” he said.

Prue raised the coffee cup to her lips and took a sip as she watched him. He couldn’t get a gauge on her and that bothered him, alternately relaxed and nervous and he couldn’t understand what caused one reaction or the other. Hallie had told him once that everything Prue did was calculated. If so, she was good, each action or reaction seeming genuine in itself, just that it made no sense when it was all put together.

He moved lightly down the hall, unsnapping his holster and removing his pistol as he did so. There had been no sounds from upstairs since he arrived; if there had been an intruder inside the house, he or she was probably gone. But the gap between probability and certainty was wide. And dangerous. He thought again about Prue at the table watching him. She was playing a game, had probably been playing one since the moment she called the station. But he didn’t know what her game was, and if there was even the slimmest possibility that there really was a prowler, he had to check it out.

At the top of the stairs was a narrow landing with four doors that led to what Boyd guessed were three bedrooms and a bathroom. He paused. Nothing. He opened the first door to his left—the bathroom, long and narrow—checked behind the door and the shower curtain. Nothing. The next room was filled with boxes, a long table and two armoires on opposite walls. Moonlight filtered in through the uncurtained window, and the room felt cold. There was an acrid smell, like burnt motor oil, and a low hum that Boyd felt more in his chest than actually heard. He flipped the switch, but the single overhead light didn’t come on, so he worked his way along the wall, checking the corners before he moved on to the furniture. The first armoire was locked; the second was empty.

The third room, visible by a night-light in an outlet by the bed, looked like a guest room—bed, nightstand, narrow painted dresser, wooden rocking chair. Boyd checked behind the door, checked the closet. No other sounds than his own footsteps as he moved though the rooms. Still, he checked.

The last room was the largest, clearly Prue’s own bedroom, with a night-light in the outlet near the door, and a second one to the left of the nightstand by the bed. Boyd checked behind the door and in the closet. He could see all the corners and he’d already lowered his pistol when he noticed that the window on the far side of the bed had been raised approximately six inches.

He approached with his hand on his gun.

There was a three-foot drop to the porch roof. The window and the storm window were both open, but not far enough for anyone to squeeze through. Cold from outside barely penetrated the warmth of the room, stymied by insulated curtains and the general stillness of the night. He tried the window himself. It lowered, but it wouldn’t open any farther than the six inches it had already been raised.

After studying both the window and the porch roof below for several minutes, Boyd returned to the closet, turned on the light, and looked up. He saw a trapdoor with a pull rope attached. When he stood to the side and pulled, steps unfolded into the narrow closet space. He waited, didn’t hear anything, and went carefully up the stairs. He could have called another deputy out, gotten them out of bed, and waited while they drove across town or ten miles in from a trailer on CR54, but even then, one of them still would have had to be the first one up the ladder.

He went up fast, pistol ready, and found what he’d expected— boxes, some dust. No intruder, but he could see that dust had been disturbed on a couple of boxes and a shelf on the near wall where there appeared to be something missing, a clear spot left behind in the shape of a small rectangle.

He refolded the attic stairs, reholstered his pistol, brushed nonexistent dust off his pants leg, and went back downstairs.

Chelly checked in on the way down, which meant he’d been there half an hour. “Five minutes,” he told her.

He went back to the kitchen, where he found Prue still in the same spot at the table, looking at the cooling coffee in her cup, her cell phone laid on the table as if she’d just made a call or was waiting for one. She didn’t look up until he approached the table. “Nothing,” he said as he crossed behind her and retrieved his jacket. “The window was open in your bedroom,” he said. “I don’t think anyone could have come through or gone out that way.” He shrugged into his jacket and zipped it. “There’s no one up there now. Have you been in the attic lately?” he asked.

She looked startled for maybe half a second; then she smiled, looked at the open cellar door, and said, “Yes. Last week, maybe?” Like it was a question he could answer. She added, “Cleaning, you know. Always something to put away.”

“To put something up there or take something out?” he asked.

“There’s nothing valuable in the attic,” she said, not actually answering his question. “There’s nothing up there to take.”

“Maybe.” He paused. “This is an old house. Are you sure you heard something inside the house?” He found it difficult to believe she’d imagined the whole thing. Mostly because he didn’t think of people that way. But also because Prue Stalking Horse didn’t jump at shadows or mistake the sound of a creaking door for an intruder. And then, there was the question he didn’t ask, the one that hung between them—why did you stay in the house if you thought there was someone upstairs?

Prue rose in a single fluid motion.

“When you were upstairs, did you notice anything… odd?” she asked. The way she looked as she said it was unsettling, like it was at least partly for this, this question, that she’d made the call to central dispatch in the first place.

“Odd in what way, ma’am?” he asked her. It wasn’t that he minded wasting his time—and this increasingly seemed like a waste of time—it was that it seemed like she did want something. She just wasn’t going to come right out and ask.

She seemed relaxed and cool once again. She tilted her head. “You have certain… talents, don’t you?” she asked.

For a horrible moment he thought she was actually propositioning him. Which had happened more than once. Women seemed to like him—until they figured out how much of a Boy Scout he really was.

“I mean”—she looked amused—“psychic talents. So I hear.”

“I’ve had… dealings,” he said. Hallie was the only person he’d ever talked to about his prescient dreams. Prue Stalking Horse wasn’t going to become the second.

“This house has a certain… aura,” she said. “I thought you might sense it. And if you did, there might be something you could help me with.”

“Ma’am,” Boyd said. “It is not appropriate to make nonemergency calls to emergency dispatch. People depend on me being where I’m supposed to be.”

“Well, I do think there was someone,” Prue said, though Boyd wasn’t sure he believed her. “Just not… problematic.”

“I’ll make another circuit outside,” he said, “before I leave.” He was tempted to issue her a written warning about the emergency call, but she’d just say she really did think there was a prowler and it wouldn’t go anywhere or make any difference to her anyway.

She walked back up the hall with him. “I’m sure it’s fine,” she said. “Maybe it was a raccoon.” She opened the front door and walked out onto the porch with him, flipping on the porch light as she came.

Something poked at him, like the undercurrent of an approaching storm, something not right that he couldn’t articulate, about the way she was acting, about one of the rooms upstairs, about something he’d seen that didn’t entirely register. Prue opened the porch door and a blast of icy winter air rushed in. “Thank you for coming,” she said.

He walked down the three porch steps, then stopped and turned back. He meant to tell her it was no trouble to come out, that it was his job.

He meant to tell her to be careful.

The crack of a rifle shot and the burst of blood on Prue’s forehead happened simultaneously. In one swift motion, Boyd grabbed her around the waist and threw her to the porch floor. He scrambled for the light switch and plunged them both into darkness. His breath came quick and sharp, puffing out in bands of silver. It was the only sound in the room other than the soft hiss of the storm door closing slowly on its pneumatics. He slid back to Prue and took her wrist. She had no pulse.

He hadn’t expected one.

“Chelly,” he said quietly into his radio. “Shots fired.” He gave her Prue’s address.

“What?”

Whatever she’d trained for, prepared herself for, thought she knew how to handle, it hadn’t been those words. She probably hadn’t heard anything remotely like them since she started working night dispatch for Taylor County or probably ever in her life. “Oh. Jesus.”

“Chelly,” Boyd said. His voice was still quiet, but insistent. Steady too, and he appreciated that, because his heart was thumping so loud, he was having trouble hearing. “Call the sheriff. Wake him up. Tell him Prue Stalking Horse has been shot and give him this address.”

He heard her take a deep shuddering breath. “Okay. Yes. Okay. Jesus.” Then she was gone.

Boyd figured it would be at least fifteen minutes before anyone arrived. He sat tight up against the inside wall with his pistol drawn as Prue’s body turned cold beside him and waited.

I really enjoyed the first two books, and am looking forward to this one, too!

Yes. Can’t wait. Maybe I should re-read the first two as a warm up……….